It was living in the shadow of a post-industrial cityscape that made me realise it was possible for dystopias to be genteel. Growing up in a nation embedded in layers of ritual, rote learned communal memories and historical truisms, it was the sight of weeds pushing through Victorian masonry and rusted iron in great defiant bushes which struck me, like a ray of enlightenment, that the land I had grown up in (sixth largest world economy, land of Shakespeare and Magna Carta) was but a nation quasi-apocalyptic.

To clarify.

There was no mistaking the sympathetic echoes of a post-apocalyptic aesthetic that permeated the urban materiality of my home cities. Buildings like half finished ruins, either on their way down to the earth or up to the sky; walls emblazoned with ghostly imprints, some of century old adverts, others of company branding blanched by relentless drizzles and the curiously acidic sun that shines but rarely heats.

It’s still strange to me, as someone who grew up in the last dregs of ‘Cool Britannia’ that once that had been a thing. Throughout my young adulthood, the country I called home seemed distinctly tepid, a nation carrying on whilst also enduring a weird unseeing of the rot behind the newly erected glass facades.

Nothing exemplified this more for me than this: that there we were, black bodies wandering through streets which still sung of their former bloody glories, unabashed by their present state. We walked as singularities, moving evidence of a temporal collapse where the mostly forgotten yet implacably grim past stakes its reality onto the future.

To survive the unspoken grotesque at the heart of this grimgreen and pleasant land, some of us turned to the newly opening realm that was cyberspace. Slowly but surely as we gently prised through the broadband barrier, the dial up tones became but a distant reverberation as we gorged and were eventually engorged ourselves. We, the black holes of faith-based histories, created social media, developing methodologies fantastic of promulgating our presences, our words, our music, our histories at the speed of light. As our siblings were layering tremulous tones and sampling to underlay thick tales of truth and mirth, we also flipped and cut and scratched with forum posts, tweets and tumblrs.

When Eshun describes AfroFuturism as, ‘...characterized as a program for recovering the histories of counter-futures created in a century hostile to Afro- diasporic projection and as a space within which the critical work of manufacturing tools capable of intervention within the current political dispensation may be undertaken’

I am often reminded about being black and wandering through the streets of Britain’s great cities, just as we also wander through the corridors of the internet. We walk as the long shadows of a failing futurism, which nonetheless acts as fuel for our own futurist projections whether in the form of poetry, street art or legislation. Ours is an Afrofuturism which regards the choice to act as either poet or seer of the black diasporic experience, but eventually shrugs and goes back to reading, is what can be described as Mundane Afrofuturism or, Afrofuturism of the Eternally Unimpressed.

After all, to be black British, or black European, is to find oneself denied any right to the body politic of the land, by omission and politely deliberate erasure. There is an additional entangling when one realises that it is the state of the quasi postcolonial that has resulted in the quasi-apocalyptic. Neither the post-colonial nor the apocalyptic state are as of yet fully complete, yet nor are they necessarily in balance. But they are entangled nonetheless, as the laws of international commerce prove. To be black British, or black European, is to find oneself walking amongst the remains of a past futurism that steeped in the viscera of the oppressed as it was, had almost no choice but to eventually falter and sink.

And yet, it is from other, mostly forgotten pasts that we AfroFuturists, Mundane or Spectacular, often draw from when confronted by the bizzarity of the genteel apocalypse. In Martine Sym’s 2015 video ‘The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto’, we hear a voice tell us that ‘[in] crises you can not only introduce new things but you can pick up elements of the new vision which were marginalised in the previous one1’, which aptly describes how as though lost for options, we first look over our shoulders at the looming ancestral presence to say »can you believe this?«, and they, muffled, kiss their teeth and half shrug, revealing glimmers of treasure in the movement of their deathrobes.

That treasure we seize upon and extrapolate and slice and scratch into, gilding with modernist irreverence to become dowsing rods for discerning through unknown futures, quite suitable for an unseen people. For if, to quote Eshun, ‘[w]ithin an economy that runs on SF capital and market futurism, Africa is always the zone of the absolute dystopia’, how much more are her children, already identified as sinkholes of white modernity, living dystopias with our hair too crinkly and ‘crazy’, our skin too dusky, our gazes too dark. If the AfroFuturist project is to ‘recognise that Africa can exist as an object of futurist projection, to paraphrase, then the side effect can only be to reclaim the black spectacular that both creates and is created by it.

Earth is all we have. What will we do with it? // The most likely future is one where we only have ourselves and our planet2

But we are here to architect futures, not to be reappropriated and have our ranking bumped a bit higher in the racial hierarchy. For if there will be black people in the future3, there must first be black people in a present. And that present belongs to the Mundane AfroFuturist.

The AfroFuturist aesthetic is one in which mainstream temporal logics are clearly suspended. Sun Ra4 arrives from Saturn crowned by a glittering nemes and robed in no doubt solar powered robes of some ethereal fabric; Betty Davis5 is a futurist sibyl, her crown a glorious afro as she bedecks herself in floral shapes with inlays of electrum; Janelle Monae6 moves with footwork that summons up the spirits of James Brown, Michael Jackson and Sammy Davis Jr.

When we critique the crumbling cities we live in, the ruins of concrete socialist utopias that did not take into account the almost cyclical rousing of modernised feudalism reflected in the deliberate diversion of tax money from councils, we can critique not with dreams of colonies in the cosmos, but knowing we can tap into ancestral knowledge of designing for complex environments and uncertain contexts, part of our dark inheritance. The Mundane AfroFuturist can look to - and yet not solely mimic - ancestors who architected cities according to structures not discovered by western mathematicians until the 20th century. For, as the mathematician Ron Eglash7 has famously described, the non-integer dimensionality of the fractal, one of the key mathematical technologies that apply to contemporary systems from cryptosecurity to video game graphics, was the basis of much of traditional architecture in pre-colonial African towns and cities. From our hair plaits to our printed fabrics, the math textbooks of yore are there to be read by those who wish to be retaught.

Similarly, in an age where an increasingly automated service network has the potential to continually entrap the black body, forced to continually absorb the fluctuating haze of enciphered prejudice, the Mundane technologist need not rely on familiar development paradigms to ensure their tech continues to learn from its mistakes, rather than repeat and amplify the soft bigotry of its makers. We don’t have to be trapped in the same tired cycle of luddite vs transhumanist. For as evidence of the first failed global futurism, we understand technologies as something deeper than pervasive computing and lovingly polished chrome, but as something that is as much a part of humanity as the mind and hands that envisaged and manufacture it8, something that, like law, religion and race, could naively be thought of as invisible technologies if not for the lasting neurological and endocrinological impact such structures have when in contact with the black body.

The joy of AfroFuturism is that, whether as a methodology allegorical or speculative, there is room enough for the Spectacular and the Mundane to work their means throughout our current temporal context. Cyborg Mama Wati’s9 can live alongside the vertical gardening urban farmer, and the local 3D printer can be just as helpful to rig out contraband imitations of Black Panther figurines as it can be for DIY laboratory equipment. We who were denied a place of our choosing in this modernity, are free to appreciate the ironic beauty that it is the marginalised knowledge of the past which bolsters our new post-modernities.

And so, as we resurrect ancient alphabets10 and mould them to fit our post-colonial inflections and as we queerify attempts at respectability politic, the Mundane AfroFuturist can rest assured that they are indeed doing their part to ‘[create] temporal complications and anachronistic episodes that disturb the linear time of progress.’ For in some ways, it is by allowing ourselves to be invigorated by our previously disowned pasts (thanks Hegel!), that we are bringing to a disappointing futurism a new way of seeing, being, encoding.

AFRICAN FUTURISMS

International Festival

Meetingpoint africa

Stadtwerkstatt: 20. - 22.09.2018

Symposium. Film. Music.

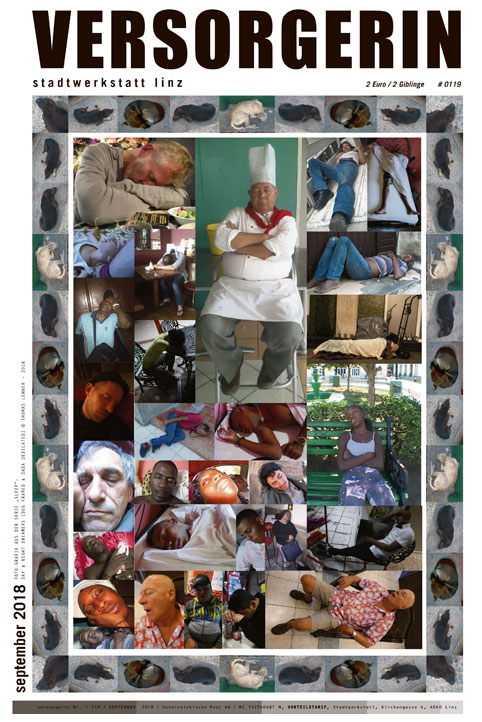

The fourth issue of Treffpunkt Afrika of the Kulturvereinigung Stadtwerkstatt with this year‘s focus on »African Futurisms« will offer insights into African visions of the future and utopias in the field of art & culture.

»The future of our planet is shaped by current trends on the African continent,« Cameroonian intellectual Achille Mbembe is completely convinced of an »Africa«, contrary to the predominant »Western« representations of Africa as a hopeless continent.

How do artists create and imagine the most diverse visionary utopias on the African continent and in the African diaspora?

In their role as Time Travellers, some of these artists and artists from the fields of contemporary art, music, science fiction literature, etc. will bring us closer to their futuristic projects and offer us space for discussion.

Festival venues are the premises of Stadtwerkstatt and Ars Electronica Center. The festival is curated by Sandra Krampelhuber.

Festival homepage: http://africanfuturisms.stwst.at