"Softness relates to sharpness like hope to oversaturation", Robert de la Sizeranne (1866-1932)

The Hofrat said: “Spooky, what? Yes, there’s something distinctly spooky about it.”, Thomas Mann (1875-1955), The Magic Mountain, Chapter 5

Starting in 1978, Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto created a cycle of fascinating photographs of historic movie theaters (published in 2016 under the title »Theaters«). He used only one light source to illuminate the interiors: the reflective cinema screen. However, its bright white glow visible in the photographs did not result from projection with white light. Instead, a complete film was played during each long exposure. The bright, neutral white screen of the photograph thus »shows« or »contains« the entire film and thus becomes a memory image of unseen cinematic »reality« neutralized in the compressed sequence of individual frames. The historic movie theaters with their empty rows of seats are bathed in Sugimoto‘s images in a soft, almost supernatural light.

Sugimoto‘s memory images create an atmosphere of shadowy melancholy, abandoning the usual concreteness of cinematic images (with all their implications from plot to - idealized - sharpness). Photographically visible is an afterglow that transforms the cinema spaces into a new reality. Hardly any other medium is as dependent on the effect of immediate presence as film. In contrast to the photograph, the cinematic frame always serves to propel an event forward. At the moment of its projection, it is already directed toward the next image. Sugimoto also radically abolishes this temporal dimension in his photographs.

The visual assurance of the temporal (especially in movement) is not only in cinema one of the essential prerequisites of the power of visual representation. This fact with all its, often rather dubious, aesthetic connotations has long since eaten its way into our - above all digitally influenced and animated - everyday life. The moving image becomes a deceptive reference to concrete existence. A circumstance that gained even more relevance during the lockdowns due to the permanent, forced evasion into pictorial substitutes.

Analog autonomy of images

With her reflections on and attempts at a post-glow cinema, or rather this year‘s work »Nik, the Sleeper«, Tanja Brandmayr attempts to counter these technologically complex procedures of pictorial production »en masse« with what she calls a »fundamentally different« strategy. One of several inspirations for her engagement with the combination of video/film projection and the phenomenon of luminescence was an exhibition by Astrid Benzer on the occasion of the Festival of Regions 2017 in Marchtrenk (specifically Benzer‘s work »Was war...«). This combined photography and phosphorescence. The common interest led last year to a joint project, this year again to two respectively different works in connection with afterglow (see info box, also two other projects). Tanja Brandmayr continues the afterglow cinema as a video projection on phosphorescent screen.

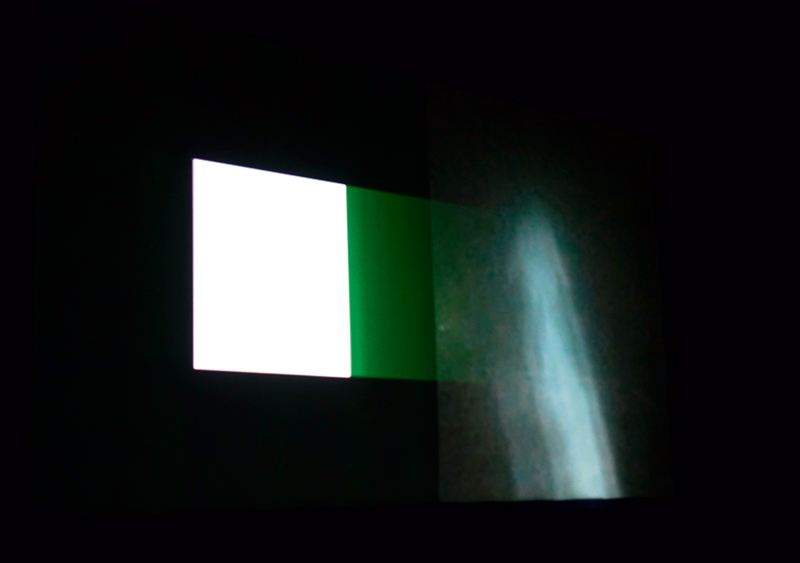

The technical principle used by Brandmayr is conceivably simple. Concepts, abstract structures, figures and scenes are projected onto a screen coated with luminescent paint. The projections, which hit the screen in rapid succession, sometimes overlapping, stimulate the luminescent paint to glow greenish afterglow. This is characterized by a rapid fading of the luminosity. The motifs and their contours blur, become shadowy, and take on a magical, almost mystical character. The duration and intensity of the fading can hardly be influenced. A largely autonomous process takes place that opens up a multitude of associative possibilities. The necessary darkness associates an immediate connection to the night and its autonomous dream worlds. The waning of the luminosity can be interpreted as a symbolic memory process (in the sense of fading). Spatially, the self-luminous forms go at a distance from the viewer. The canvas shows a light that is only conditionally able to encompass us spatially and to define our position in space. Through this renunciation of spatial definition and readability of things (in terms of sharpness and contour), we are placed in a mode of reception that is designed for atmosphere, transcendence, and mood. In the light we are accustomed to in everyday life, a clearly defined reality confronts us. The soft, blurred »mood images« of Postglow, on the other hand, seem more like a mirror of inner states of mind, even dreamlike. From the many possible interpretations that postglow cinema opens up, the following section will focus primarily on the aspect of blurriness.

Blurred mood images

The described characteristics of Tanja Brandmayr‘s post-glow cinema, and also of Astrid Benzer‘s photographic approach, place them in a line of tradition that discovers blur as an alternative in the course of industrialization and the increasing, detailed possibilities of perception and depiction of reality. The cult of blurring finds its aesthetic starting point in the invention of photography before 1850. With increasing technical improvement, the photographic image was able to achieve an accuracy of reproduction and image sharpness »per shutter release« that could only be achieved with difficulty through painting and drawing. The claim of visual art to be the sole means of capturing reality and nature no longer existed. Artists felt this development to be quite crisis-ridden and increasingly turned to representational means that led away from technically precise photographs. As an alternative, the use of blur virtually forced itself upon them. Photography followed suit only a short time later in order to achieve comparable effects.

The sharp image brings the world to a focus on the immediately perceptible presence of spaces and objects. It tells a precise story. The eye wanders from object to object (information to information) and assembles the individual elements into a logical whole. This unambiguity of perception and its transformation into a »narrative« image is diminished or prevented by the use of blurring. Realism and »truthfulness« of a representation are shifted by the blur in favor of mood and atmosphere. Consequently, for the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl (1858-1905), the cult of blurring observed around 1900 corresponds to a »modern need for mood.« The blurred image opens up hardly calculable (soul) effects in the viewer and thus eludes the paradigmatic demands of modernity for precision, measurability, and information efficiency.

Our own present is characterized far more than any previous epoch by the permanent availability of the »sharp« image (in a broad sense including every form of information; keywords: big data, metaverse, networking, etc.). At the same time, some groups, surprisingly using the same media passionately, are currently formulating an extremely problematic skepticism toward everything factual (keywords: hostility toward science, conspiracy, esotericism, etc.). Reality is - if one believes these »skeptics« - increasingly untrustworthy. The resulting social and cultural blurs have long since become frighteningly destructive factors. If the turn to blurriness around 1900 was at least partly an attempt to soften the hard contours of the reality of life and thus to open up new horizons or spaces of possibility, today it leads to an existential endangerment of social realities and arrangements.

Of course, it is always problematic to set phenomena of different epochs with their different preconditions in parallel. But when Tanja Brandmayr lets her analog, self-luminous »images of consciousness« shine forth, this naturally also formulates a visual-media counter-thesis to the technically flawless images of our digital reality construction and experience. Brandmayr‘s afterglow cinema follows a spatio-temporal dynamic that can only be controlled or manipulated to a limited extent. In this way, it differs in a sympathetically low-tech way from the technologically dominated, destructive constructs of digital alternative »realities.« The autonomy presented in Postglow finds its point of reference in the spheres of the unconscious and the dream, which can only be influenced to a limited extent. For all its abstractness, the shadowy afterglow becomes a visual resonance surface for individual states of mind.

Comforting magic: a kind of epilogue

At the end of a manageable odyssey through various vacation destinations (and the search for love), Delphine, a Parisian secretary, ends up in Biarritz and meets Edouard, just before the final abandonment of her trip. Delphine (played by Marie Rivière), with this encounter, at the end of Eric Rohmer‘s 1986 film Le Rayon vert (The Green Ray) and after the endless slide and monologues of his heroine, typical of Rohmer, plunges into a kind of magical consciousness. Now, for Delphine, it is no longer a matter of linguistically (logically?) penetrating and explaining one‘s own existence and need for love (as if one could yak one‘s happiness away). Instead, she sits with Edouard »au bord de la mer« and together they watch the sunset. This one is now to have it in itself: Delphine waits for the fabled green glow that, depending on the weather, becomes visible for a split second immediately after the sun disappears below the horizon line. The green glow does indeed appear, and Delphine recognizes it as the longingly awaited magical sign of her personal happiness. The rest is credits.

Bei STWST48x8 DEEP. 48 Hours Disconnected Connecting sind 4 Projekte zu sehen, die auf verschiedene Weise mit Nachleuchten arbeiten:

Nachleuchten / Bewegtbild:

Tanja Brandmayr: Nik, the Sleeper

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/nik_the_sleeper

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/en/nik_the_sleeper

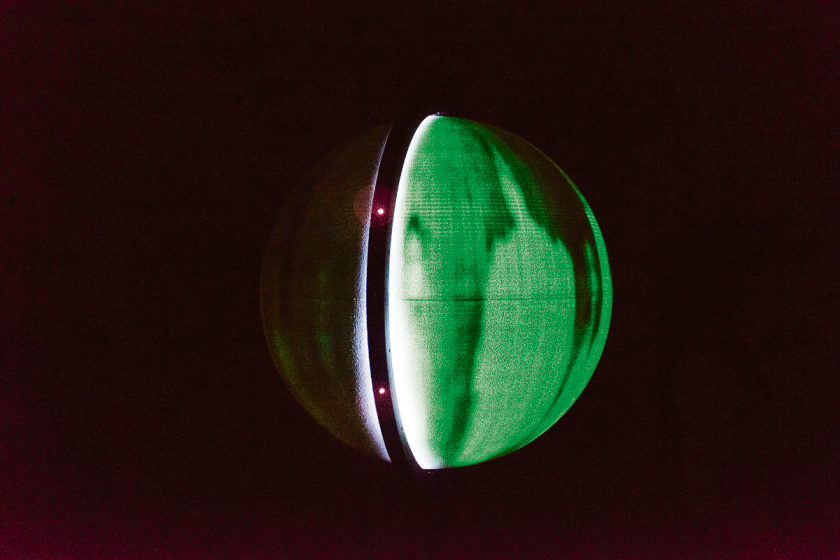

Gregor Göttfert, Florian Kofler: Sphäre

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/sphere

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/en/sphere

Nachleuchten / Installation:

Astrid Benzer: Luminophorium, Prototyp 1.0

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/luminophorium_prototype_1.0

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/en/luminophorium_prototype_1.0

taro: entitate luzitransis [№ I+II]

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/entitate_luzitransis_i_ii

https://stwst48x8.stwst.at/en/entitate_luzitransis_i_ii